Forest Loss in South East Asia

how to use this page

Scrolling over the article in this part of the page will jump the 'main panel' to the right to different chapters. Scrolling over the visualizations within the 'main panel' to the right will animate the visualizations of forest loss.

Over the last 20 years, we've lost almost 1,000,000km2 of forests. Despite this being a significant reduction from the peak deforestation levels of the 1980s, that's still an area the size of Egypt.

Currently, we deforest about 100,000km2 each year: an area the size of Iceland. We reforest about half as much, which means that global net forest loss is about 50,000km2 per year (the size of Costa Rica)

This page explores the causes and impacts of forest loss in Indonesia and Malaysia: two areas of key environmental significance. Rainforests in Indonesia are home to over 17% of the world's species, despite accounting for just 1.3% of global landmass.

By providing habitats and sinking huge amounts of CO2, the rainforests and peatlands of South East Asia are a vital and fragile component of our global ecology. Since 2001, Indonesia has lost over 18% of its tree cover: an area the size of Nevada.

There are lots of reasons for this deforestation: ranging from policy reforms and economics, to environmental concerns and geopolitics. This report combines 20 years of satellite-derived forest loss data with geopolitical data-points: showing where, when, and how forests have changed in South East Asia since the turn of the century.

Indonesia at the turn of the century

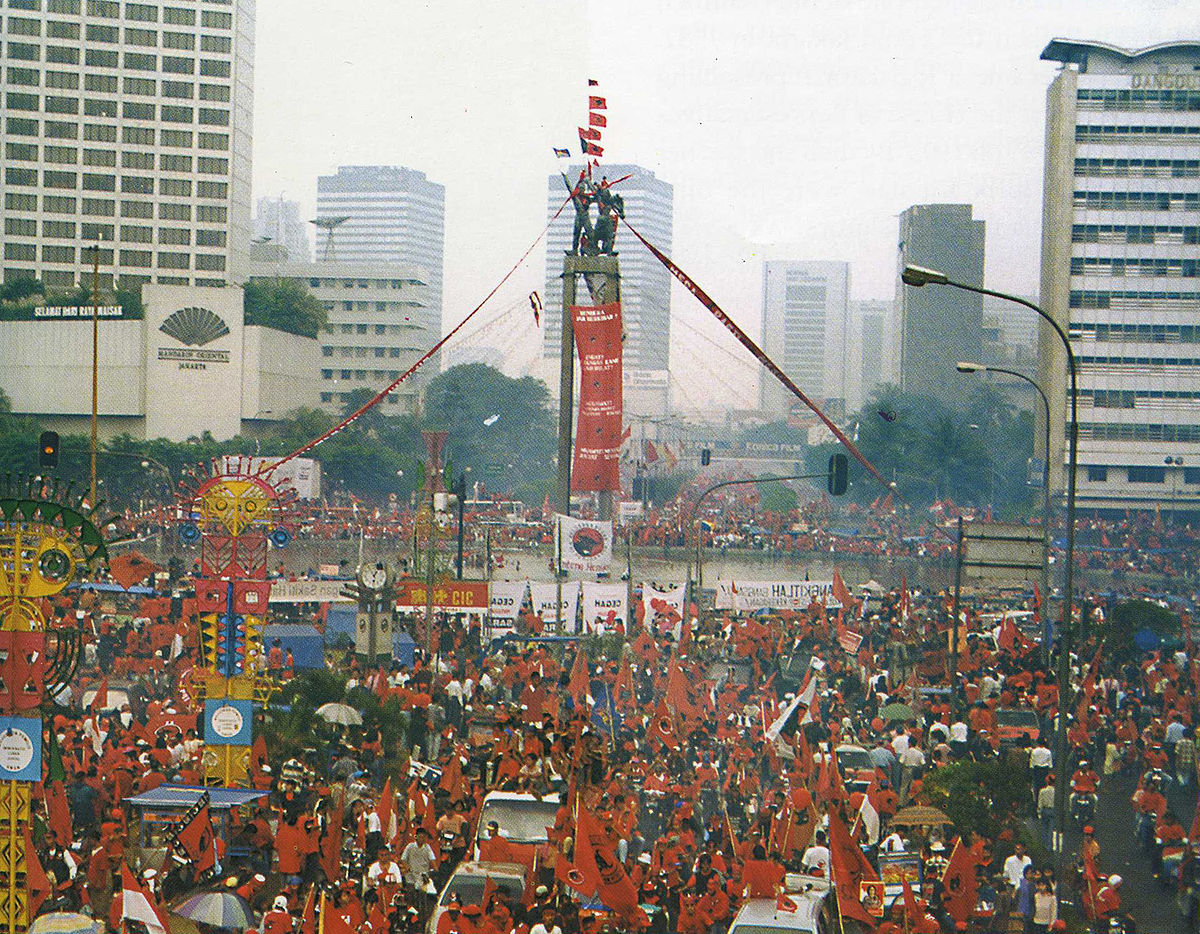

It's 1998 in Indonesia, and two major events are colliding. Firstly, the recent Asian Economic Crisis of 1997 has devalued the Indonesian Rupiah by 80%, and led to a 13.6% economic contraction.

Additionally, a record-setting 1997-98 wildfire season has destroyed millions of hectares of forest, costing USD$8 billion , releasing up to 2.57Gt of carbon, and significantly harming crop yields. The resulting economic turmoil from these events provokes widespread rioting in May 1998, and ultimately leads to the fall of the 31-year New Order dictatorship.

2000-2002

The Reformasi Period

A newly formed interim government is given a clear mandate: turn Indonesia from an authoritarian regime into a democracy. There's tremendous public pressure to promptly hold official elections for the new government, but there's lots of administrative and legislative reform that needs to happen first.

In the months that follow, legislation is rushed through that aims to prop up the agricultural sector, which is battling high inflation, low yields, and a global decline in the price of crude palm oil (CPO).

In response to the previous regime's mismanagement of the industry, the interim government decides to stimulate agricultural production by reducing export taxes and withdrawing from commercial decision-making. This period, known as the Reformasi Era, is defined by legislation that relinquishes governmental authority over forest resources to regional governments.

2003-2005

Logging Concessions

The laissez-faire 'Reformasi' period gives district authorities the ability to grant forest-clearing concessions. The aim of this policy is to stimulate economic growth and stabilize the agroindustrial sector, but the result is that logging concessions become political tools for local governments facing re-election.

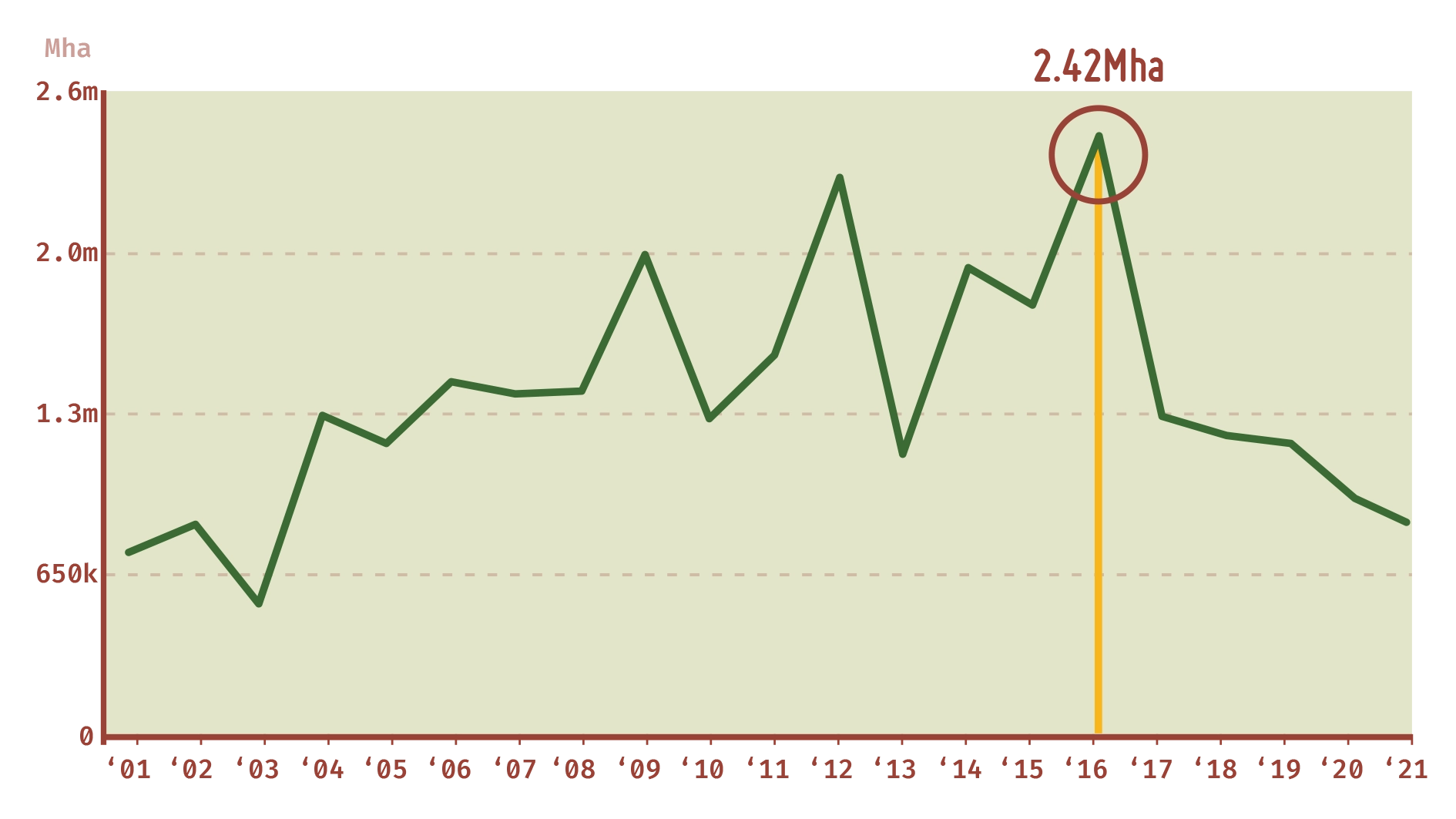

In 2003, The World Bank raises concerns about the Indonesian decentralization strategy. With local governments incentivized to boost the economy and secure re-election, logging concessions become the primary driver of deforestation in Indonesia, and by the end of the year, Indonesia has the highest rate of deforestation in the world, reaching 2.4 million ha/yr.

At this time, an estimated 90% of Indonesian Timber is illegal, with large amounts of timber smuggled into China to fulfill demand in the international furniture market (link). Tolerance of illegal timber operations is also an issue due to lost tax revenues that could otherwise be collected by the government.

By 2004, the MoF (Ministry of Forestry) regains authority over forest concessions with the passing of law 32/2004.

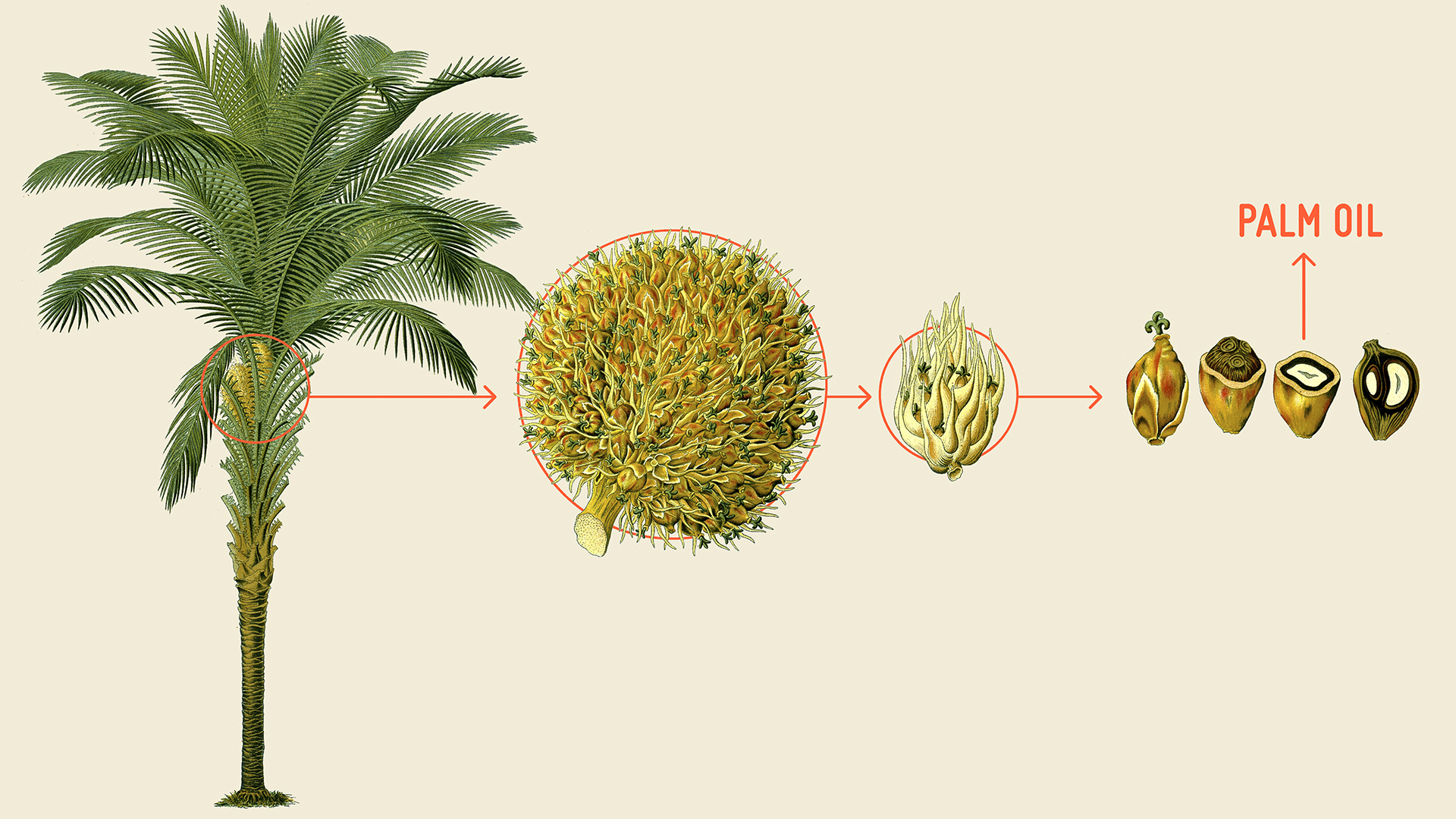

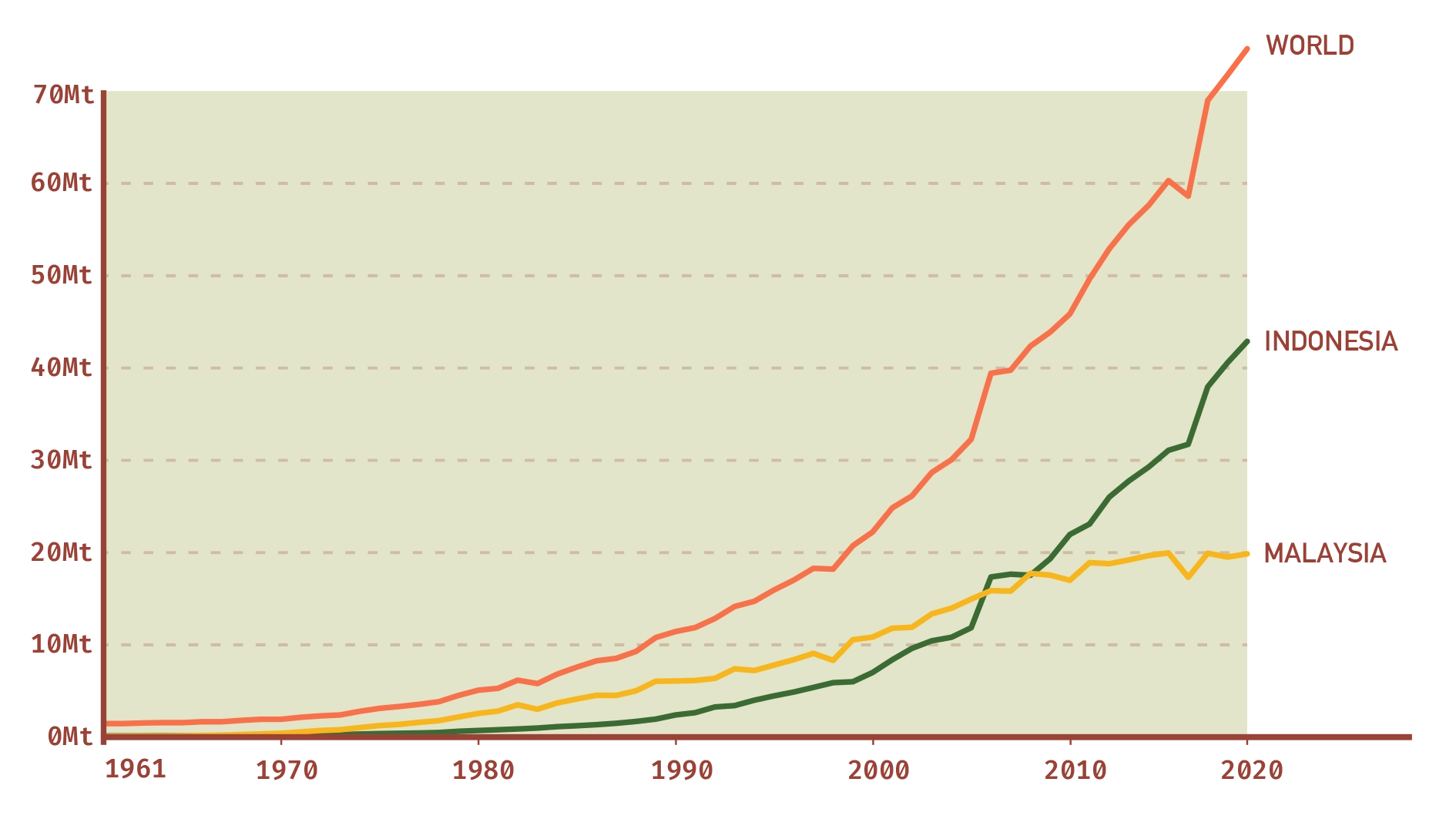

The growth of Palm Oil

During this time, Palm Oil has increased in popularity, driven by the growth of demand from China, and the desire of Western markets to phase out hydrogenated vegetable oils in favor of healthier options. The low cost, remarkable efficiency, and natural saturation of Palm Oil makes it an ideal replacement, and by 2005, oil palm plantations surpass timber to become the primary driver of deforestation in Indonesia.

To address the responsible development of palm oil, the RSPO is launched in 2004, as a non-profit organization that provides certification to Palm Oil plantations that meet their criteria.

Palm Oil Expansion

In 2005, the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry sets targets to expand logging and palm oil exports. Logging areas are set to increase from 2.5 to 5 million hectares, and palm oil is set to increase from 5 to 8 million hectares by the end of the decade (the USDA estimates that 7.65 million ha of plantation was reached). Market forces make palm oil the most favorable export, which leads Indonesia to take the place of Malaysia as the global leader in palm oil production in 2007.

2006-2010

Forest Clearing Accelerates

Despite ongoing ecological warning signs, the pace of forest clearing continues to accelerate, and by 2007, Indonesia has lost 72% of its intact ancient forests. Forest loss is compounded by the burning of forest to make way for plantations - a practice called Slash & Burn that makes remaining forest more vulnerable to future fires.

Burning carbon-rich forests also releases a lot of stored CO2. into the atmosphere, and sends a toxic smog drifting towards population centers. As production increases in South East Asia, so too does slash and burn, and between 2008 and 2009, forest fires increase by 200%.

A Decade of Deforestation

Forest loss in the first half of the decade averages 932Kha per year. By 2010, this rate has grown to 1.437Mha per year. Total Oil Palm plantation area reached 7.65Mha - 96% of its 2005 target to increase its plantation area from 5 to 8 million hectares. With palm oil prices jumping by 175% in a decade, the incentives for forest clearing are greater than ever.

2011-2015

Logging Concessions

In 2010, Norway pledges $1bn to Indonesia if forest conservation goals are met. This marks a shift in the public messaging of the Indonesian government, which in 2011, introduces a temporary moratorium on logging contracts in carbon-rich peatlands and primary forest.

A Change of Leadership

In 2014, Joko Widodo is elected as the president of Indonesia, amidst projections of a slowing GDP, and high expectations for reform.

Conservation efforts are ongoing, but progress is slow. The situation is complex: climate policy is tied to economic pressures - and as conservationists push, the government pushes back. Implementation proves difficult too - the moratorium is limited in scope, and doesn't affect existing or unlicensed plantations.

Between 2011 and 2015, it's estimated that the moratorium had a 1.5-2/2% impact on emissions from deforestation, making the government's 2020 target of 26-41% that much more difficult to achieve.

The number of RSPO-certified plantations are increasing, but slowly. At this time, approximately 3 million hectares of plantations are certified, representing 19% of plantations. The European market is the key customer for Certified Sustainable Palm Oil (CSPO), although importantly, 2/3 of the Palm Oil imported the EU in 2015 is used for biofuel; a practice generally understood to be worse for the environment than petrol (when land use changes are factored in).

2015 Wildfires

The ongoing practice of slash and burn, coupled with the dry conditions of the particularly late 2015 El Nino event, sparks some of the worst forest fires the region has ever seen. The World Bank estimates that 2.6 million hectares of Indonesian land burned in 2015 alone, and the fires take more than 100,000 lives. The resulting haze affects a number of South East asian countries, spiking respiratory and cardiovascular conditions.

By the end of the year, India becomes the world's largest importer of Palm Oil, behind China and the EU.

2016-2020

Forest Fire Aftermath

Twenty-three companies face consequences from the Indonesian government in the immediate aftermath of the 2015 fires, which are estimated to have caused more than $16bn of damage. Ashes left behind by the fires form fertile soils, and large swathes of land are converted to agricultural grasslands. Coupled with the loss of a further 2.42Mha, Indonesian deforestation levels in 2016 are the highest on record.

The Paris Agreement, signed in 2016, provides directives on rainforest protection, and enshrines important frameworks such as REDD+ into international policy.

The following year, primary forest loss in Indonesia drops by an unprecedented 60%. This is primarily due to two factors: the relative decline from the abnormally high 2016 levels, and the Indonesian government's conservation policy efforts. The 2016 creation of the Peatland Restoration Agency, and the subsequent national Peat Drainage Moratorium, are introduced in reaction to the 2015 fires. The moratorium requires concession holders to protect areas with more than 3m of peat, and rehabilitate that which has already been cleared.

Clearing in these newly protected areas drops by 88%, leading to a reduction in forest fires driven also by a long wet season. Sub-national elections, and the 2017 Asian games may have also played a role in the change of direction.

Conservation momentum continues into 2018, with a 3 year moratorium on all new Oil Palm plantations introduced by President Jokowi. The 2011 moratorium on concessions in protected lands is made permanent soon after in 2019, and forest clearing continues to drop to 1.22Mha/yr.

The substantial progress made is not without its problems. Illegal logging is still prevalent, and legal loopholes persist. These practices continue to cause forests to burn, and in 2019, the government reports that 1.6mmha were destroyed by such fires. A further study reveals that the area is closer to 3.1mmha, raising questions about the government's transparency in its reporting of the data.

Conservation progress is further threatened by changes in legislation. The 2019 rescission of peatland protection measures reduces the zone of protection to only the peat-dome, while the Omnibus law, passed in November 2020, leads to protests over the reduced environmental protection measures within.

Impact

Where do we go from here?

Forest degradation is a complex problem: intractable from economic development, environmental protection, and growing global demand. Palm Oil remains the most efficient vegetable oil in the world - and demand is only set to grow as our global population increases.

Nevertheless, considerable progress on responsible forestry has been made in the region. Deforestation in recent years has dropped dramatically, and the establishment of initiatives such as the Peatland Restoration Agency is a positive sign. However, targets aren't always met, and promises aren't always kept. The PRA, for example, met only 45% of its 2020 restoration target, before it was renewed, and a promising pledge made by over 100 world leaders at COP26 to end deforestation by 2030 was dismissed just a few days later by the Indonesian Environment Minister, citing unfairness and economic priorities.

Meanwhile, the climate continues to change. Another season of wildfires in 2019 released over 700 million tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere, adding to the habitat destruction and air pollution that endangers wildlife and human wellbeing in the region.

The stage is set for an extremely important few years in our forests. From grassroots organizations and local innovation, to big data and ambitious policy measures - it's more important than ever that we work towards a balance between environmental and economic concerns.

Work with Crossground on Palm Oil

Crossground continues to engage in projects related to Palm Oil. Organizations interested in partnering, especially on earth observation and data-driven conservation, are encouraged to reach out at