monarch butterflies

how to use this page

This page has two panels: this one contains the article, and the panel on the right is for interactive media. Scrolling in either panel will advance the story, and jump the other panel to the correct section.

The Monarch Butterfly of North America is an important pollinator, providing vital

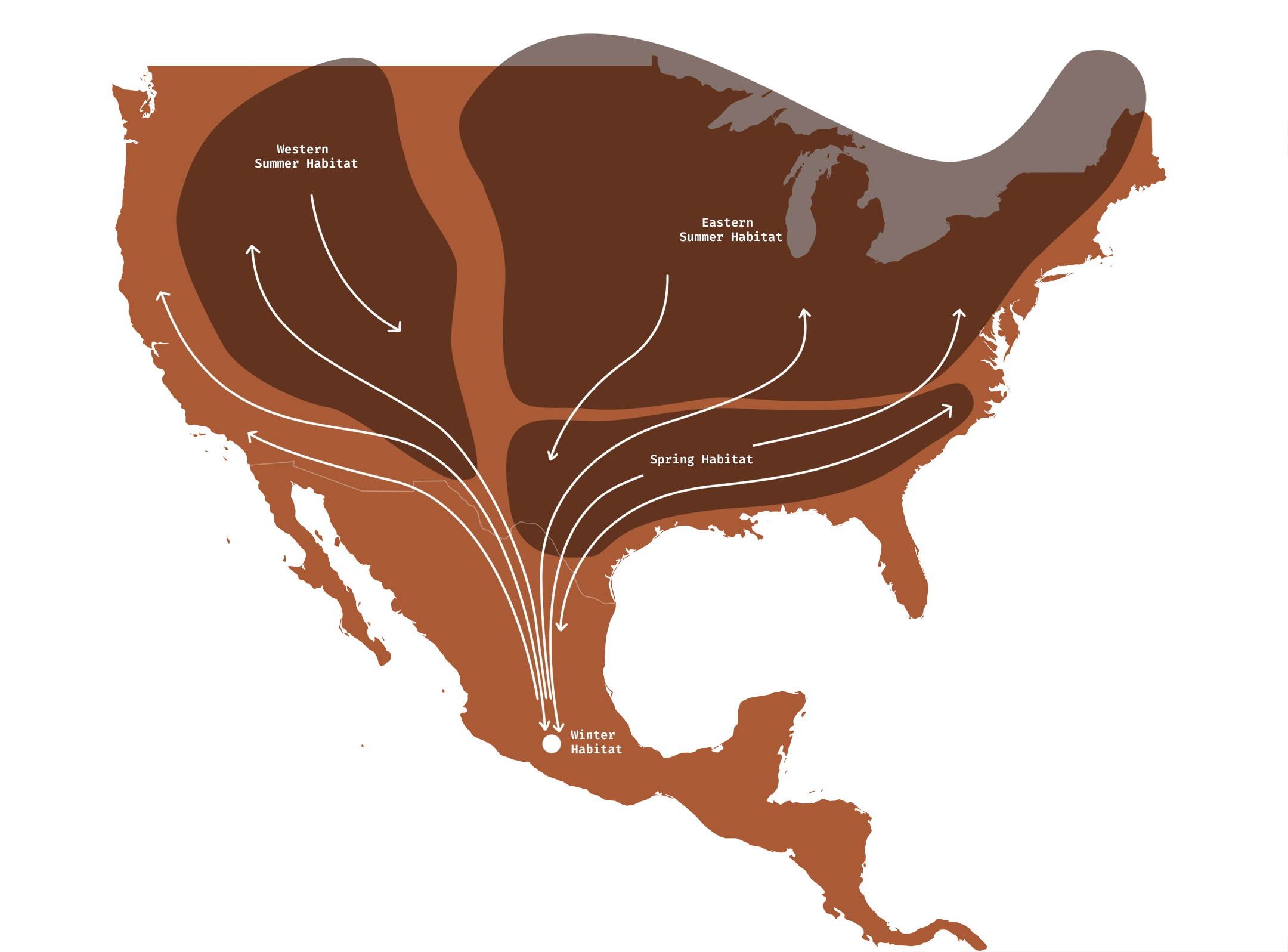

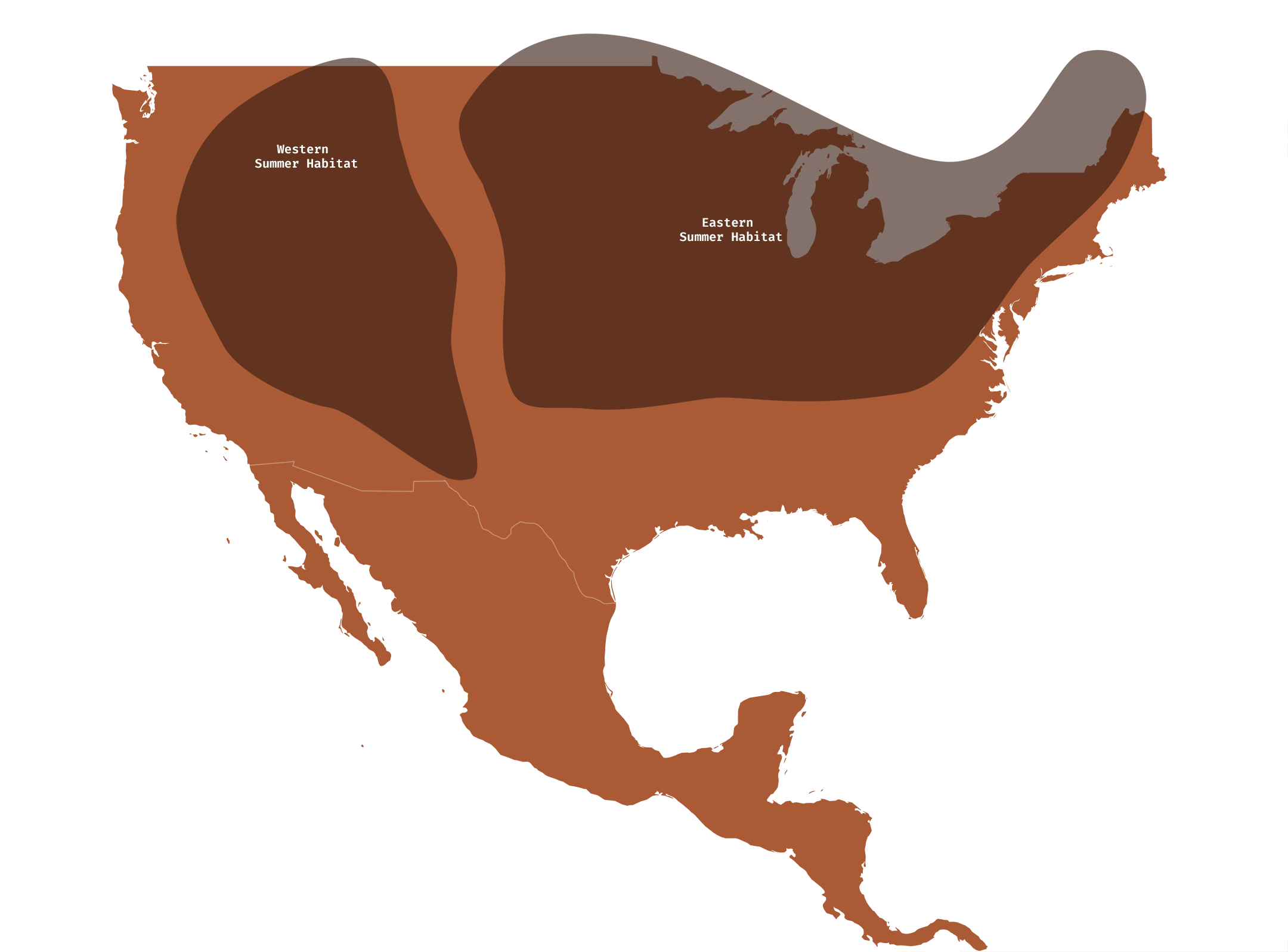

A 3000 mile migration

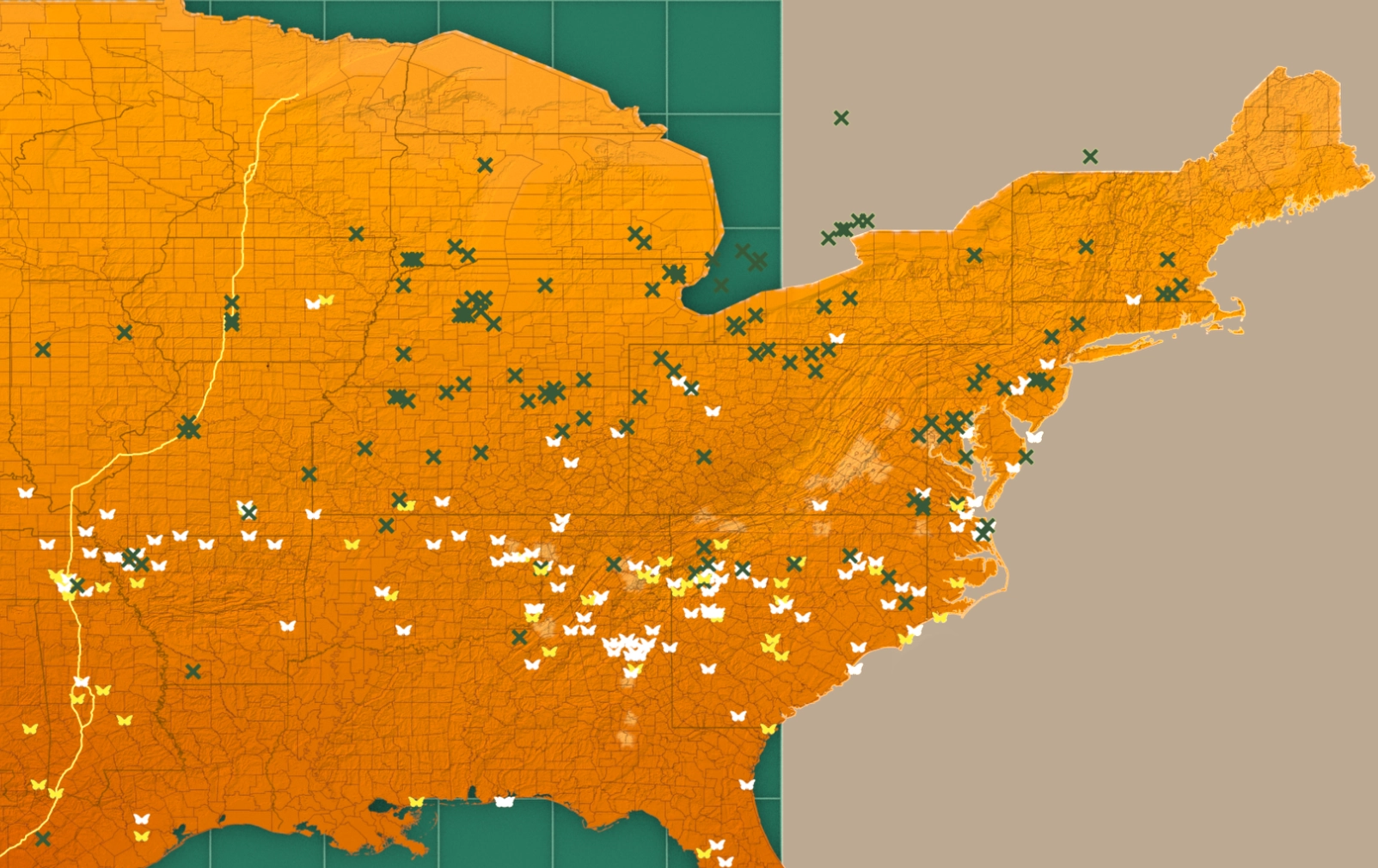

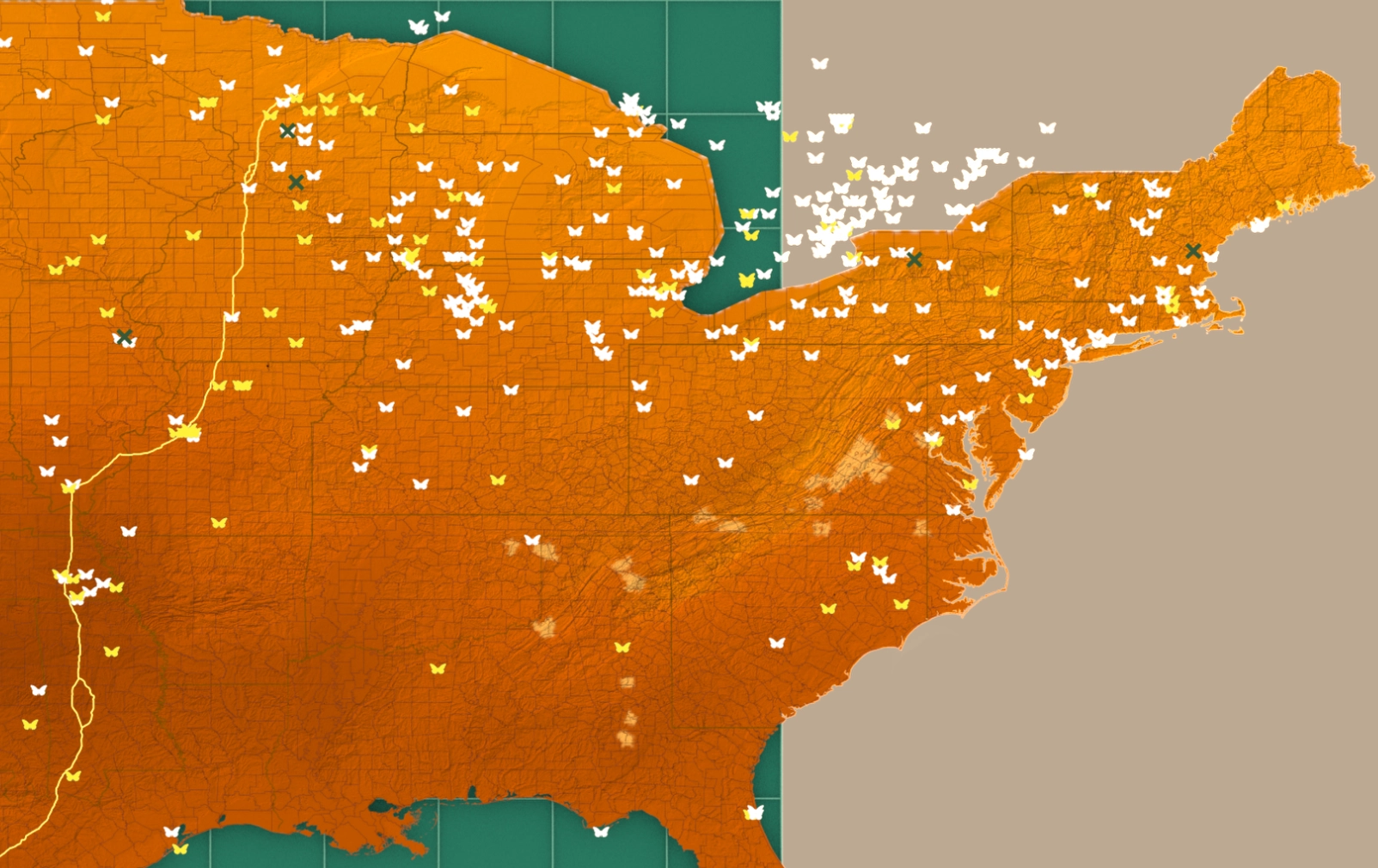

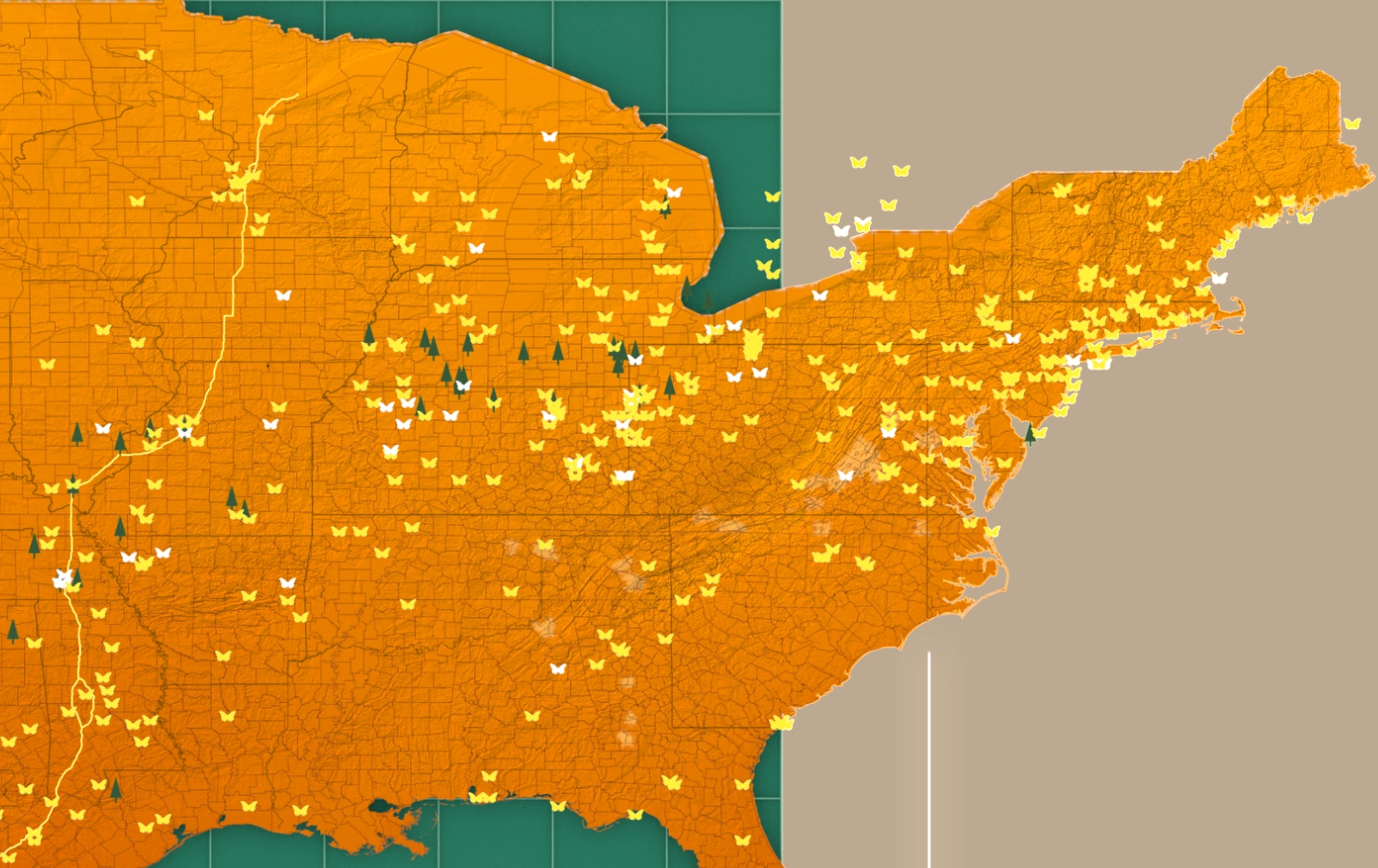

Each year, monarchs journey from their winter habitat in Southern Mexico to breeding grounds in the US. Sightings are recorded by citizen scientists throughout the region, and made available by Journey North.

| record | data | town | state | latitude | longitude | number | type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 07/21/20 | La Mesa | CA | 32.8 | 0117 | first-milkweed | |

| 2 | 07/29/20 | Aurora | CO | 39.6 | -104.8 | milkweed-all | |

| 3 | 07/31/20 | Allenton | WI | 43.4 | -88.4 | 1 | monarch-spring |

| 4 | 07/31/20 | Mocksville | NC | 35.9 | -80.5 | 1 | egg-spring-first |

| 5 | 07/31/20 | Coram | NY | 40.9 | -73 | 5 | egg-spring |

| 6 | 07/31/20 | Arnold | MD | 39 | -76.5 | 5 | larvae-spring |

| 7 | 12/31/20 | Eastpoint | FL | 29.7 | -84.9 | 1 | monarch-fall |

| 8 | 12/31/20 | Brenham | TX | 30.2 | -96.4 | 3 | eggs-fall |

| 9 | 12/31/20 | Orlando | FL | 28.5 | -81.5 | 2 | larva-fall |

| 10 | 11/10/20 | Monterrey | NLE | 25.7 | -100.3 | 200 | monarch-peak |

The map to the right animates over 20,000 of these over the 2019 migration. Each feature is represented with a different icon.

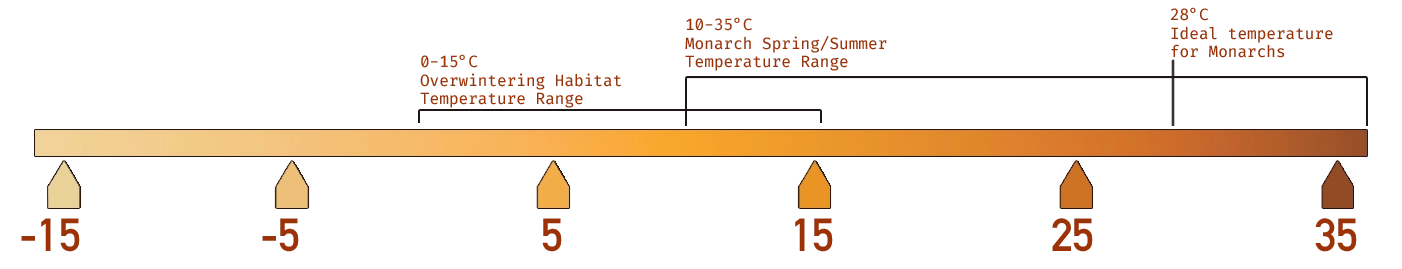

As temperatures increase in spring and summer, Northern US states become habitable for monarchs, and they are able to migrate further north. Monthly county-level temperature data from NOAA shows how these thresholds impact the migration.

| name | FIPS | state | jan | feb | mar | apr | may | jun | jul | aug | sep | oct | nov | dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fairfax | 51059 | Virginia | -1.385 | 3.545 | 7.18 | 14.22 | 19.245 | 23.555 | 27.835 | 25.255 | 21.34 | 13.13 | 9.485 | 5.88 |

| Radford | 51750 | Virginia | -1.415 | 4.19 | 6.94 | 14.145 | 17.53 | 25.19 | 25.19 | 23.89 | 19.55 | 12.17 | 9.29 | 5.59 |

| Washington | 51191 | Virginia | -0.87 | 4.325 | 7.69 | 14.13 | 17.305 | 21.75 | 24.05 | 22.765 | 19.175 | 11.74 | 9.135 | 5.745 |

| Araphoe | 08005 | Colorado | -0.16 | -0.345 | 7.39 | 9.7 | 12.665 | 21.785 | 26.5 | 26.045 | 18.675 | 12.3 | 5.38 | -0.98 |

| Williamsburg | 51830 | Virginia | 1.235 | 5.815 | 8.54 | 16.115 | 8.54 | 25.185 | 28.165 | 26.56 | 22.83 | 15.605 | 11.525 | 8.11 |

| Roanoke | 51161 | Virginia | -1.135 | 4.56 | 7.23 | 14.54 | 18.145 | 23.39 | 26.55 | 25.2 | 20.53 | 12.91 | 9.715 | 5.875 |

| Greensville | 51081 | Virginia | 1.33 | 6.425 | 9.33 | 16.67 | 20.395 | 26.33 | 29.43 | 27.305 | 23.11 | 15.295 | 11.2 | 8.115 |

In the map to the right, county color is based on this temperature data, using the below scale.

The visualization begins in January 2019, when monarchs are hibernating in the mountains of Michoacán, Mexico. A few sightings occur in the southernmost US states, which are home to non-migratory populations.

spring

In early spring, the monarchs awake from hibernation, and are driven north by warming temperatures. As they travel, they lay their eggs exclusively on milkweed, which is considered an invasive species in the US. The milkweed provides monarchs with a source of food, and they are able to absorb toxic

Shortly after, we see an explosion of monarchs in the US, and by mid May, they can be found as far north as Canada.

summer

By August, conditions are ideal, and monarchs are at the maximum extent of their summer range. The Rocky Mountain range splits the monarchs into a large eastern, and smaller western population.

fall

Each monarch has a lifespan of about four weeks, and so the journey from spring to fall has taken three generations.

The fall generation, however, is different. Known as the super generation, these monarchs will undertake the entire return journey to southern Mexico, arriving in mid-November to hibernate for the winter.

This super generation travels together, becoming more densely packed the further south it gets. As this happens, colonies of monarchs will roost together in trees throughout the US: most notably along the I35 interstate highway.

winter

By November, the monarchs are mostly back in Mexico, where they will hibernate for the winter. The colony roosts on the Oyamel Fir trees in the mountain forests of Michoacán.

With the vast majority of monarchs gathered in a small area, it's possible to estimate their annual population.

How are Monarch numbers changing?

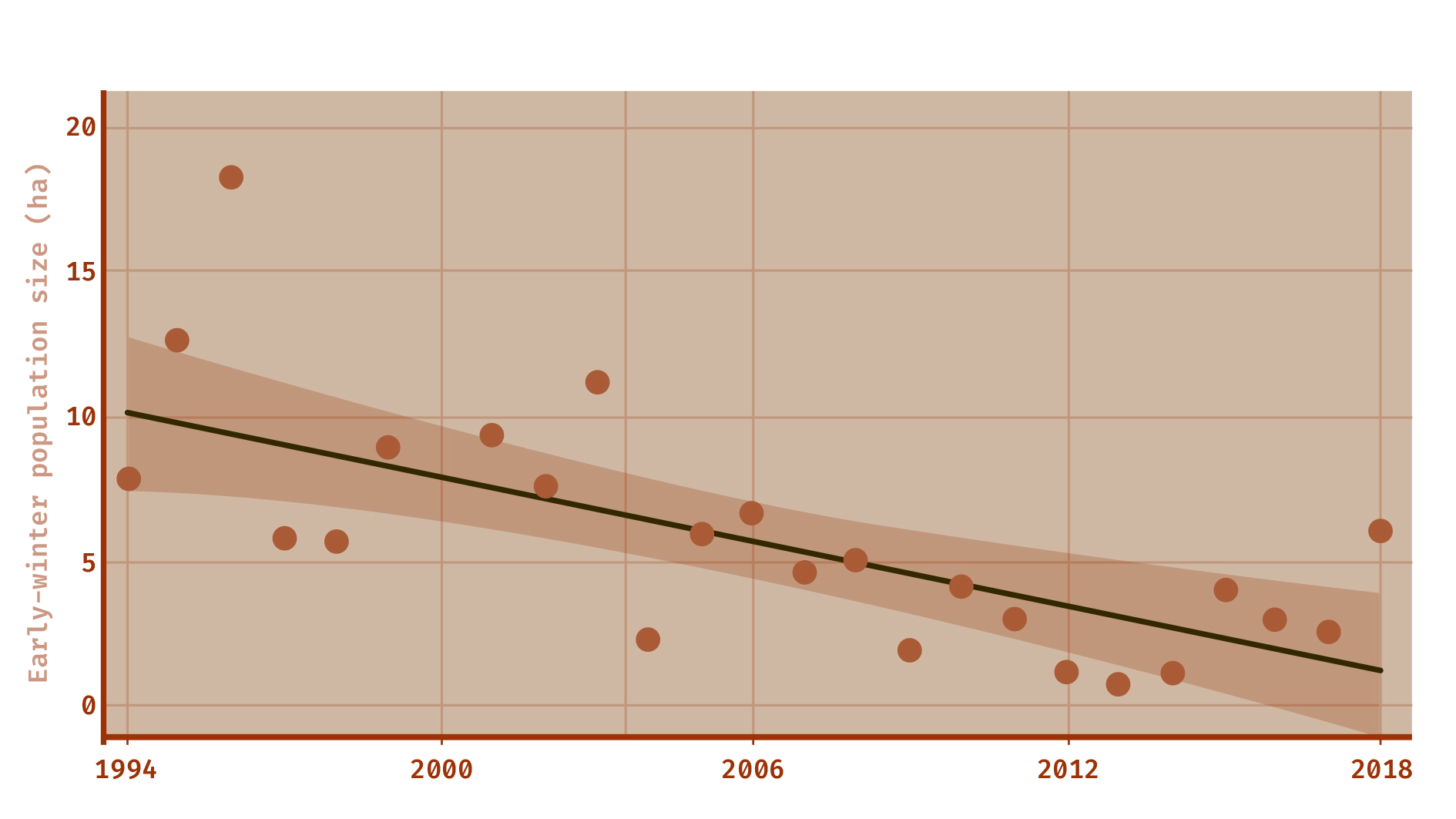

There are too many monarchs to count individually - so the area of their winter colony is used instead.

The overall size of these colonies has been plummeting: by more than 80% in the past 30 years. The sharpest decrease happened in the 1990s, before a steady decline throughout the 2000s and 2010s.

The visualization to the right animates these changing colony areas over the past 30 years. While the population has been represented here as a single colony, there can be up to 20 separate colonies spread throughout the mountain forests each year.

Reasons for collapsing Monarch Numbers

There are three common hypotheses for why monarch numbers are declining: tough migration conditions, milkweed habitat loss, and climate change.

A 2022 study from the Zipkin Quantitative Ecology Lab analyzed the contributions of each factor to the overall effect. It's findings are summarized below:

1. Tough migration conditions

The 'Migration Survival Hypothesis' proposes that tough migration conditions such as disease, winter habitat loss, and reduced nectar availability leads to lower migration survival in the fall super generation.

The hypothesis was developed in response to data that suggested a lack of correlation between summer and winter population sizes. The reasoning was that if the summer population is not directly related to the size of the winter population, then the migration that happens in between could be the reason.

The grounds for this hypothesis may have been flawed: The study found that the size of the summer population accounts for 90% of variance in winter population size, with the variance attributed to nectar and forest loss under 10%.

2. A loss of Milkweed Habitat

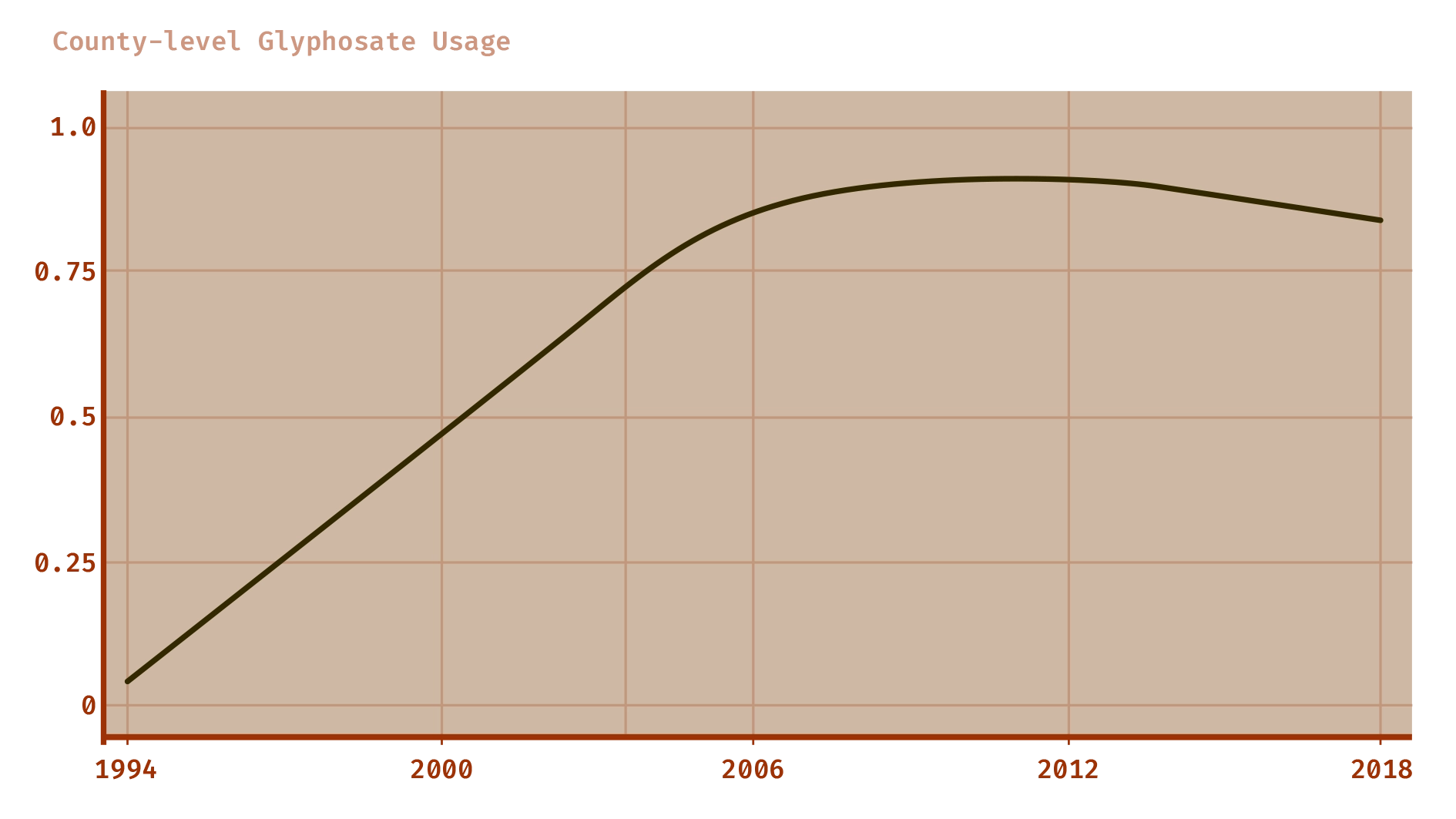

The 'milkweed limitation' hypothesis proposes that monarch numbers are declining because of a massive loss of milkweed.

Milkweed is the only plant on which monarchs lay eggs. It's usually found on the fringes of agricultural fields, but because it's an invasive species, farmers are incentivized to kill it with herbicides.

Before the 1990s, the amount of herbicide that farmers could spray was limited, because spraying too much could also kill crops. With the introduction of

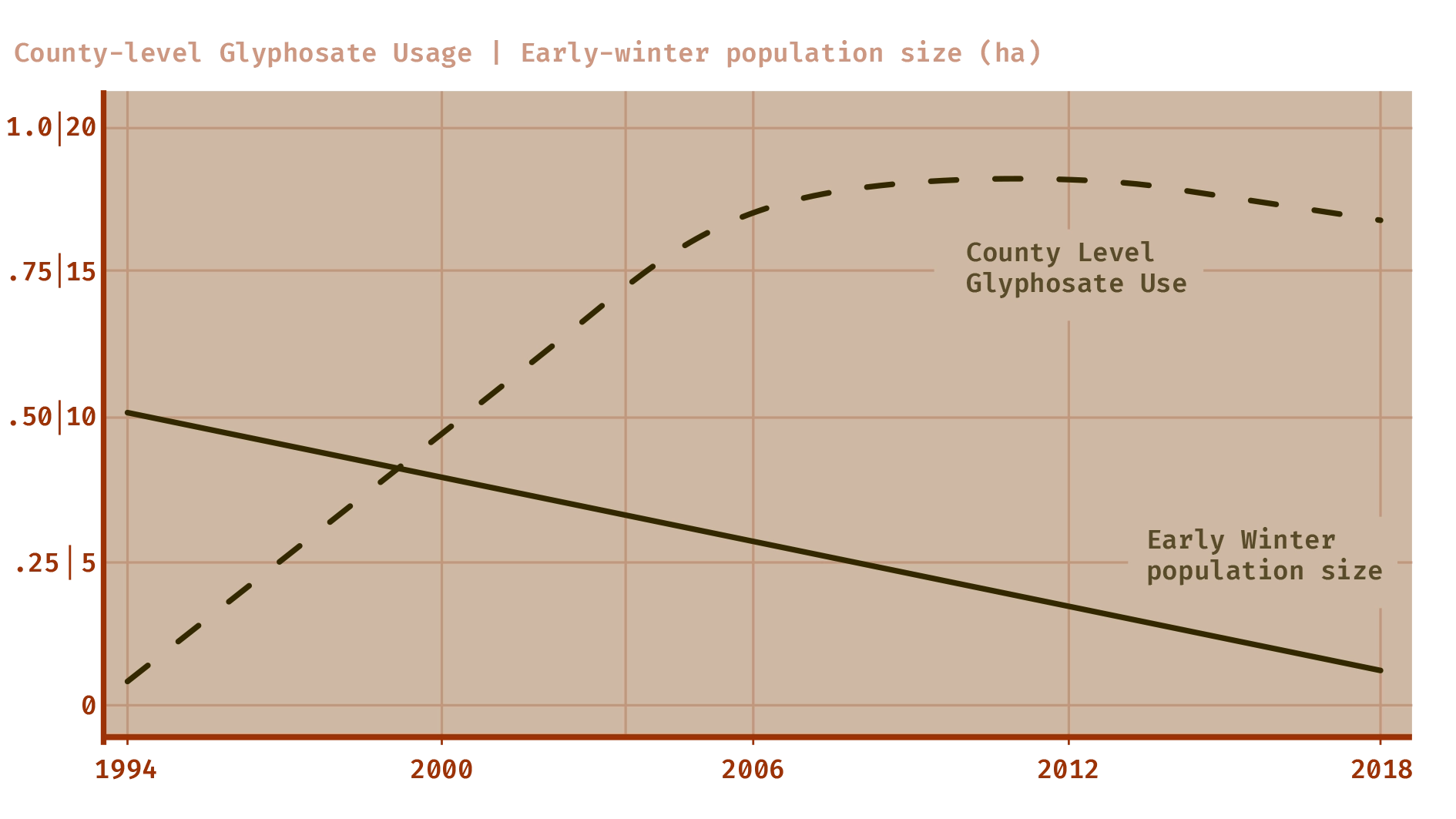

Monarch population numbers declined most sharply in the 1990s, coinciding with the widespread adoption of glyphosate-resistant crops in the US. As glyphosate usage leveled off in the 2000s, monarch numbers continued to steadily decline, suggesting that while impactful, milkweed abundance alone doesn't explain the ongoing collapse.

3. Climate Change

Taking a wider view, we can project that the climate in North America is likely to become more volatile throughout the 21st Century. Increased volatility introduces significant risks to biodiversity, but especially to migratory species.

For monarchs, there are a few notable climate impacts. In particular, weather patterns in spring and summer affect fertility, survival rates, and milkweed abundance. Changing climate conditions in southern US states such as Texas are especially important to track, as the majority of monarchs pass through these areas.

The Zipkin study found strong support for the climate change hypothesis from 2004-2018. Weather conditions in the spring and summer explained the most variance in monarch population numbers, and are seven times more important than other factors.

What's best for Monarchs?

While the future for the monarch butterfly is uncertain, it's clear that variations in climate, herbicide usage, and habitat loss will significantly impact their numbers.

In low-emissions scenarios, we can expect the climate in the US to be warmer, with similar precipitation patterns as we see today. In higher emission scenarios, it's likely that southern and western states like Texas and California will become more hot and dry, while eastern states will become wetter. Northern states will get warmer more quickly, and as a result, we may see the monarch range shift north.

From year to year, continued variation in monarch numbers is expected. Like many climate-related problems, the increasing frequency of events that would have previously been considered outliers is a key concern. Sustained exposure to these outlier events can trigger an irreversible

Collecting targeted data can reduce uncertainty in statistical models, which in turn helps organizations more accurately target conservation schemes. In particular, there are gaps in spring-time data, because it's harder to collect when the monarchs are more geographically distributed.

Focusing habitat restoration efforts in areas where the habitat is likely to remain favorable to monarchs will be a key strategy for preserving the species. Organizations like Monarch Watch run programs that create habitat along the migratory path, and integrating grass-roots efforts like this with better data can maximize their impact.

Reframing milkweed as a productive crop instead of a weed is also a potential solution. Milkweed produces a silky floss, which can be used as an insulative filler. Exploring the applications of this material could create the necessary incentives for milkweed to become a commercial crop. If correctly aligned with conservation efforts, the cultivation of milkweed across the US could offset the need for non-commercial habitat restoration.

Work with Crossground on Monarchs

Crossground continues to engage in projects related to monarch butterflies. Organizations interested in partnering, especially on data-driven conservation strategy and milkweed valorization, are encouraged to reach out at